Sacred Nudity to Body Shame

What role did Christianity play in Western Gymnophobia?

Introduction

Did Christianity cause Western society's endemic fear of nudity? Many British naturists conclude the answer is yes. Yet historical evidence reveals a contradiction: during Christianity's initial centuries, believers underwent completely naked baptism ceremonies presided over by church leadership. This practice, documented by multiple church fathers and considered theologically essential, continued until approximately 700-800 CE. How did a religion that once celebrated ritual nudity as symbolizing spiritual purity become synonymous with body shame?

Contemporary Christian naturist organizations like Naked and Unashamed and the Christian Naturist Fellowship argue for returning to earlier understandings, claiming body shame represents distortion rather than Christian essence. This essay examines Christianity's complex relationship with the human body from biblical times through the Middle Ages, Victorian era, and to contemporary movements. It demonstrates that the issue involves philosophical infiltration, cultural anxiety, conflation of modesty with shame, economic forces, and genuine theological evolution—not simple religious prudery.

Part One: The Biblical Era and Early Christian Reality

Eden's original vision

Genesis 2:25 establishes humanity's created state: two people existed naked without shame. The Hebrew word carries connotations of openness, integrity, and absence of shame. However, Genesis 3:1 describes the serpent using a linguistically connected word meaning cunning. This wordplay suggests disruption came through deception, not bodily exposure.

Shame entered only after the Fall. When God asked Adam "Who told you that you were naked?", only four beings were present. Contemporary Christian naturists emphasize the devil, not God, introduced shame about nakedness.

Christian naturists argue that Adam and Eve covered themselves from fear of divine judgment for disobedience, not bodily shame. When God provided garments of animal skin, this represented practical protection in the harsh world outside Eden, not moral requirement. As the CNF states: "God mercifully clothed mankind out of physical necessity, not moral necessity."

Contextual nudity in scripture

Biblical attitudes toward nudity were contextual rather than uniformly negative. Isaiah walked naked and barefoot for three years at God's explicit command. King Saul prophesied naked all day and night, described without moral condemnation. Sexual nakedness outside marriage and forced nakedness representing poverty carried shame, but functional and ritual nudity were accepted matter-of-factly.

Jewish ritual bathing and Christian adoption

Jewish ritual bathing (mikveh) required complete nakedness for immersion. Jewish law strictly required removal of all clothing, jewelry, and makeup—any barrier between body and water. Hundreds of stepped pools from the Second Temple period have been discovered, with earliest purpose-built structures dating to the 1st century BCE.

Early Christianity inherited this tradition. Saint Hippolytus of Rome documented around 215 CE that baptism candidates must remove all clothing and jewelry. In the 4th century, Saint Cyril of Jerusalem described immersion in baptismal pools after stripping. Early catacomb paintings depict naked baptisms without scandal.

Saint John Chrysostom (c. 400 CE) explicitly connected baptismal nudity to Eden: stripping reminded candidates of their former Edenic nakedness. The theological rationale held that baptismal nudity symbolized returning to Edenic innocence, represented death and rebirth, connected to Christ's naked crucifixion, and mirrored Jewish mikveh tradition.

The Greco-Roman cultural context

Early Christianity existed within Greco-Roman culture where certain forms of public nudity were normalized. Ancient Greece celebrated athletic nudity through gymnasiums. Romans developed massive public thermae (baths) central to social life. By the 1st century CE, mixed-gender nude bathing was common. A 354 CE catalogue documented 952 baths in Rome alone.

However, Roman attitudes were ambivalent. Complete public nudity could offend in certain venues. This contradiction between functional acceptance and contextual concern would influence later Christian developments.

Part Two: From Sacred Nudity to Body Shame

Augustine's theological revolution (4th-5th centuries)

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) fundamentally changed Christian attitudes toward the body through theological extrapolations dominating Western Christianity for over a millennium. Augustine taught that original sin transmitted through sexual intercourse itself, specifically through concupiscence (lust) inherent in sexual acts. He wrote: "Those who are born from the union of bodies are under the power of the devil ... because they are born through that concupiscence by which the flesh has desires opposed to the spirit."

Augustine argued that before the Fall, Adam could procreate purely through intelligent choice without passion. After the Fall, sexual desire became uncontrollable and disordered. He interpreted Genesis 3 to mean that shame arose regarding nakedness as an affection common to beasts.

Augustine was heavily influenced by Neoplatonism and Stoicism. Neoplatonic philosophy viewed the soul as good and matter as evil. Combined with Stoic concepts of controlling bodily passions through mental reasoning, these ideas were subsumed into his Christian theology. In 418 CE the Council of Carthage adopted his views on original sin, thereby questioning the legitimacy of nakedness during baptism.

However, Augustine used Neoplatonism to argue for creation's goodness, not against it. His target was Gnostic heresy teaching that matter and bodies were inherently evil. By the 4th century, Christians employed Neoplatonism as "one of their chief weapons for affirming the goodness of the created world."

The Carolingian turning point (750-900 CE)

The most dramatic shift occurred during the Carolingian period. Named after Charlemagne, who became King of the Franks in 768 CE and Holy Roman Emperor in 800 CE, this era saw sweeping reforms imposing Roman liturgical standards on Western churches and centralizing religious authority. Christians were still often baptized naked until this standardization.

The standardization process outlawed naked baptism on grounds of immodesty, marking where nudity itself began being seen as inherently sexual. The period witnessed widespread penitentials—handbooks for confessors—meticulously categorizing and condemning sexual sins, intensifying morality focus and making public bathing's uncontrolled environment seem dangerous.

After Louis the Pious's death in 843 CE, the Roman Empire contracted rapidly. Clothing became a crucial social status marker and "civilization" indicator, contributing to ecclesiastical and societal views equating nudity with the profane or uncivilized, contradicting the earlier sacred perspective.

Religious art transformed as well. Christ began depiction clothed on the cross, contrasting with earlier historically accurate naked depictions. The practice associating Christian nudity with grace and spiritual purity was replaced with viewing nudity as inherently problematic.

The High Middle Ages (12th-13th centuries)

The High Middle Ages witnessed unprecedented asceticism proliferation. Thomas Aquinas advanced Augustine's views, teaching that "sexual desire was shameful not only as original sin, but that lust was a disorder because it undermined reason." Sexual arousal was deemed so dangerous it "was to be avoided except for procreation."

The 12th and 13th centuries saw extreme ascetic movements. Saint Bartholomew of Farne proclaimed: "We must inflict our body with all kinds of adversity if we want to deliver it to perfect purity of soul!" Female ascetics practiced severe bodily mortification: Catherine of Siena practiced severe fasting and self-induced vomiting, ultimately dying from refusing food and water.

Despite growing body shame, nude public bathing remained common. Roman baths in Bath, England, "were used by both sexes without garments until the 15th century." Church attitudes were ambivalent as many church fathers promoted cleanliness as Godliness prerequisite.

The Renaissance and Counter-Reformation backlash (14th-16th centuries)

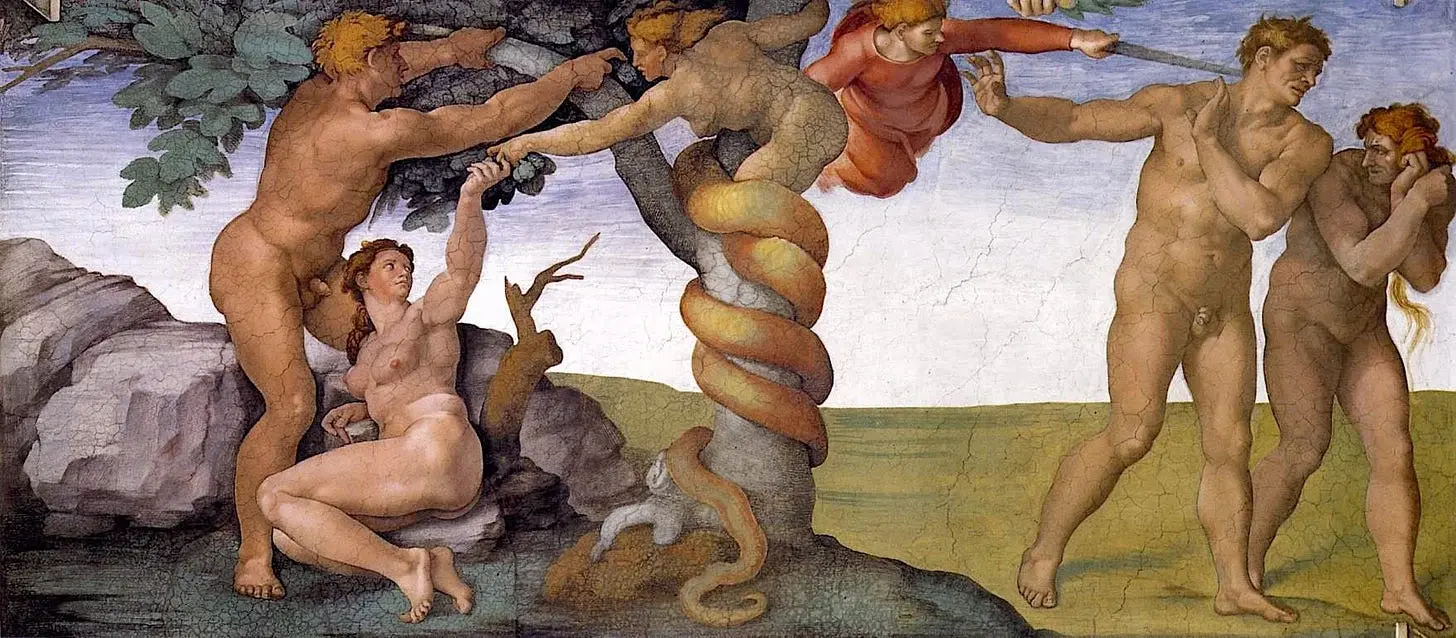

The Italian Renaissance brought renewed interest in Greco-Roman culture. Donatello's David was the first fully nude sculpture since antiquity. Michelangelo's famous David was celebrated yet controversial. Artists argued for nude human form dignity and beauty as reflecting divine creation.

Catholic popes initially patronized nude art. However, Michelangelo's Last Judgment, featuring hundreds of nude figures, prompted fierce controversy. The Council of Trent's 25th Session issued decrees prohibiting "all lasciviousness" in religious art. Almost all nudity was forbidden, including infant Jesus depictions. Daniele da Volterra painted over nude figures earning the nickname "il Braghettone" (the breeches-maker). This campaign continued for over two centuries.

Protestant reformers maintained diverse attitudes. Martin Luther elevated marriage and rejected mandatory clerical celibacy, theoretically giving sexuality within marriage new dignity, though this didn't translate to public nudity acceptance. John Calvin and Reformed churches practiced iconoclasm destroying all religious art including nude works. Both Catholic and Protestant streams condemned public nudity across denominational lines.

The Victorian apex of gymnophobia (19th century)

The Victorian period (1837-1901) represented the culmination of centuries-long Christian body-negative attitudes. Public nakedness was considered obscene. Extreme modesty requirements emerged with swimming costumes requiring coverage "from neck to knees." Even Queen Victoria was scandalized by nude art, commissioning removable fig leaves for classical statues.

Christian missionaries imposed Victorian standards globally. Indigenous peoples' traditional nudity practices were condemned, equating nudity with "savagery." The Victorian era transformed earlier Christian teachings into a comprehensive body shame system: equation of all nudity with sexuality, extreme gender segregation, and bodily shame. This represented the most restrictive period in Christian attitudes toward the body since the 8th century.

However, Victorian body attitudes tied to class distinctions, industrial capitalism, overpopulation anxieties, and sexuality medicalization—not purely religious origins. The Victorian era produced extensive pornography and erotica. Victorian body shame represents a specific historical development combining Christian elements with secular anxieties.

The Purity Culture movement (20th-21st centuries)

Late 20th century saw emergent evangelical "Purity Culture," intensifying Victorian-era body shame through new mechanisms. Beginning in the 1990s with movements like True Love Waits (1993), this primarily American evangelical phenomenon promoted sexual abstinence through purity pledges, purity rings, and father-daughter "purity balls." I Kissed Dating Goodbye (Joshua Harris, 1997) became a bestseller, teaching that any romantic or physical contact before marriage damaged purity.

Purity Culture teachings focused disproportionately on female bodies and dress. Young women received instruction on covering their bodies to avoid being "stumbling blocks" causing male lust. The movement taught that women bore responsibility for men's sexual thoughts, and that women's value intrinsically tied to sexual "purity." Metaphors comparing sexually active women to chewed gum, used tape, or damaged goods became common in youth group teachings.

Research by psychologist Tina Schermer Sellers demonstrates that shame instilled through 'purity culture' parallels trauma from sexual abuse. Many who grew up in these movements report difficulty with sexual intimacy even within marriage, persistent body shame, and anxiety disorders. Several key purity culture leaders, including Joshua Harris, have publicly renounced their earlier teachings and apologized for harm caused.

While purity culture represents specific late-20th-century American evangelical movement rather than historic Christian orthodoxy, its influence spread widely through megachurches, youth ministries, Christian publications and early internet. It created a generation associating Christianity with extreme body shame and sexual repression. This context is crucial for understanding why many assume Christianity is inherently anti-body, and why Christian naturists feel compelled to argue for theological alternatives.

Part Three: Contemporary reclamation

The modern Christian naturist movement

With modern internet rise, Christian naturism became organized. The website Naturist-Christians.org founded in 1999 became the largest site devoted exclusively to Christian naturism. Annual Christian Nudist Convocations began in the early 2000s. In Britain, the Christian Naturist Fellowship provides support for Christian naturists across denominations, broadening its reach globally since the pandemic.

Chris of Mudwalkers represents modern Christian naturist activism, uniquely combining Christianity, naturism, and rewilding. His mission statement articulates the challenge: "Christianity looks back on Eden, with its nakedness and its harmony with the natural world, but doesn't embrace it. Naturism so often misses out on the Creator who gave us this wonderful world to enjoy and on the fullest integration and harmony with it. Rewilding is too often based on atheism or paganism rather than Yahweh's vision for humanity made in his image."

Chris's work includes video content, podcast appearances, and active participation in events like the World Naked Bike Ride where he and fellow Christians wore body paint with Christian messages. His tagline "naked means human" encapsulates his core argument that nudity represents fundamental human state. His "Personal Manifesto of a Christian Naturist" presents 85 propositions deliberately echoing Martin Luther's 95 Theses, providing comprehensive theological framework.

Core theological arguments

Contemporary Christian naturists present coherent biblical interpretation challenging traditional opposition. They emphasize Genesis 2:25 as foundational: God created humans naked intentionally and declared creation "very good." Nakedness reflects being created "in the image of God."

Crucially, they argue shame came from Satan, not God. Chris's manifesto states: "I believe it must be assumed that the serpent is the 'who' of 'Who told you that you were naked?' I believe 'that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world' started a lie that all of mankind has wrestled with ever since. Part of that lie is a distorted view of the body, that it is impure, dirty, lewd, or shameful in and of itself."

Regarding fig leaves, they distinguish fear from shame. Adam and Eve covered themselves from fear of God after sinning, not body shame. The fig leaves were "a futile attempt to hide what the couple had done from God—not each other, noting they were married, and equally guilty of the same original sin." God was displeased with both their disobedience and "with Adam and Eve's subsequent attempt to cover up their bodies."

When God provided garments of skin, the CNF emphasizes: "God mercifully clothed mankind out of physical necessity, not moral necessity." Clothing provided protection in the harsh world outside Eden, such as thorns and bad weather, not because nakedness itself was shameful. As Fig Leaf Forum states: "Any and every understanding of why God gave them clothes must be 'read into' the text, because the explanation of God's purpose simply is not there."

Papal developments and other historical precedents

Pope John Paul II's papacy, beginning in 1978, represented a papal shift. His Love and Responsibility stated: "Nakedness itself is not immodest ... Immodesty is present only when nakedness plays a negative role with regard to the value of the person, when its aim is to arouse concupiscence." His Theology of the Body argues "the body, in fact, and only the body, is capable of making visible what is invisible: the spiritual and the divine."

Historically, Ilsley Boone (1879-1968), a Dutch Reformed minister, founded the American naturism movement in the late 1920s, leading the American League for Physical Culture, later renamed the American Sunbathing Association in 1931. Reverend Bob Horrocks, founder of the CNF, wrote Uncovering the Image, an 80-page "definitive guide for the Christian Naturist."

Several historical sects practiced ritual nudity including the Adamites (2nd-4th century North Africa) who claimed to restore Adam and Eve's innocence, and the Naaktloopers ('naked walkers') who in 1535 ran naked through Amsterdam streets proclaiming the "naked truth."

Part Four: Critical analysis

The historical verdict

The proposition that Christianity caused Western gymnophobia is historically reductionist and empirically challenged. Early Christians practiced naked baptism for many centuries. The early Church built and maintained public baths throughout the Middle Ages. Eastern Orthodox churches still practice baptismal nudity for infants today. Multiple Church Fathers condemned promiscuous nudity but not the body itself, supporting gender-separated bathing facilities.

The evidence reveals distinct patterns. Early Christianity was not inherently gymnophobic. Medieval Christianity showed mixed attitudes following the Carolingian turning point. Renaissance and Reformation witnessed both artistic celebration and Counter-Reformation suppression. Victorian Christianity represented specific cultural-religious fusion resulting in extreme repression. Modern Christianity remains diverse across traditions.

Multi-factorial causation

Western gymnophobia arose from multiple interacting factors: specific historical Christian misinterpretations, Victorian cultural anxieties, Platonic and Gnostic theological infiltration, modern capitalism and body commodification, sexuality medicalization, media culture and impossible beauty standards, and the Purity Culture movement. None are inherent to biblical or orthodox Christianity.

Kyle Harper's award-winning scholarship From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity (Harvard University Press, 2013) provides crucial nuance. Christianity transformed sexual morality from "shame" (social regulation) to "sin" (theological accountability), revolutionizing human dignity by granting equal moral standing to slaves, women, and the poor. The transformation was gradual and more just in some ways, ending routine sexual exploitation, even though unintended consequences echo over a millennium later.

Cross-denominational evidence

Eastern Orthodox Christianity provides crucial evidence that Western gymnophobia represents specific Western cultural developments, not inherent Christian theology. Orthodox theology views nakedness as representing vulnerability and humanity before God, with no inherent shame. It maintains baptismal practices including nudity and, as Father Stephen Freeman, an Orthodox priest, affirms: "Originally, we were naked and unashamed – but we lost our original beauty."

Contemporary mainstream Christian perspectives on nudity and modesty

The vast majority of contemporary Western Christians hold views shaped by the historical developments outlined above, though perspectives vary significantly across denominations.

Catholic teaching, following John Paul II's 'Theology of the Body', affirms that the body is good and nakedness not inherently immodest, whilst emphasizing modest dress to protect dignity. The Catechism acknowledges that "modesty varies from one culture to another" and most Catholic moral theology accepts contextual nudity – such as medical settings, family contexts, certain artistic expressions – whilst maintaining that public social nudity is generally inappropriate.

Mainline Protestant denominations generally hold similar positions: the body is created good, but public 'modesty' is appropriate. These churches typically avoid detailed dress codes, trusting congregants' judgement about appropriate attire for different contexts.

Evangelical and fundamentalist churches tend towards more restrictive positions, often heavily influenced by purity culture. Many provide specific dress codes, particularly for women: prescribed skirt lengths, covered shoulders, high necklines. Some prohibit mixed-gender swimming or are highly prescriptive about swimwear.

The primary theological justification across these traditions is the "stumbling block" argument from Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 8. These passages originally addressed eating food by way of example, warning against behaving in such a way that would cause fellow believers to violate their conscience. Conservative teaching, however, makes a theological leap and applies this to dress, arguing that if one's clothing could cause another to lust and therefore violate their conscience, one should cover up out of Christian love.

This application warrants scrutiny, however. The original context concerned religious practice, not managing others' sexual thoughts. The argument assumes 'modest dress' prevents lust (empirically questionable), that women bear responsibility for men's thoughts (contradicting personal accountability), and that hiding bodies 'solves' lust rather than addressing lust itself – whilst perpetuating the Medieval idea that lust transmitted original sin and was a "disorder because it undermined reason." Furthermore, it's applied inconsistently and with prejudice: focusing almost exclusively on female bodies whilst ignoring athletic wear, dance contexts, or whether men's bodies might have similar effect on women or gay men.

But what is modesty, properly understood? Within modern Christian teaching, modesty is an internal virtue characterized by humility and non-judgmental attitude toward others. It manifests through respectful conduct and appropriate behaviour in different contexts. True modesty regarding nudity recognizes that different situations call for different standards – what's appropriate at a beach differs from a business meeting, which differs from a medical examination. Pope John Paul II clarified this: "Immodesty is present only when nakedness plays a negative role with regard to the value of the person ... The human body is not in itself shameful ... Shamelessness (just like shame and modesty) is a function of the interior of a person."

Regarding 1 Timothy 2:9 commanding modest dress, Christian naturists argue the passage addresses women wearing "costly array" and focuses on avoiding "outlandish and expensive clothing," not prohibiting those who choose not to dress at all. The context is about ostentatious display and class distinctions, not coverage per se.

Indeed, many contemporary Christians now advocate for more balanced approaches: teaching personal responsibility for one's thoughts, acknowledging cultural relativity in modesty standards, and distinguishing between sexualization and simple nudity. Some progressive Christian communities have abandoned dress codes entirely, trusting members to exercise wisdom whilst maintaining appropriate boundaries.

Body shame versus Christian teaching

A critical distinction exists between Christian teaching on modesty and psychological body shame. These are fundamentally different phenomena that purity culture and much of contemporary Christian teachings have unfortunately conflated.

Body shame is a psychological dysfunction involving fear or disgust toward one's own body, belief that the body is inherently corrupt or dirty, and often has roots in trauma. It manifests as anxiety about one's physical form, compulsive covering or hiding of the body even in appropriate contexts, and often profound discomfort with natural bodily functions. Research by psychologist Tina Schermer Sellers and others demonstrates that shame instilled through religious purity culture creates symptoms parallel to sexual abuse trauma; difficulty with intimacy even within marriage, persistent guilt about embodiment, and chronic general anxiety.

Christian modesty, properly understood, is something entirely different. It's not about fear or shame but about respect – for oneself, for others, and for context. It recognizes human dignity whilst acknowledging our social nature. Authentic Christian teaching affirms that God created the body and declared it "very good", that Christ himself took on human form (the Incarnation), and that our bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit. Body shame contradicts these core Christian affirmations.

The confusion between these concepts has deep roots in the historical developments traced earlier. None of these represent biblical Christianity's original understanding of the body. Christian naturists argue that their practice actually embodies authentic Christian modesty better than shame-based dress codes. By normalizing the human body in non-sexual contexts, naturism separates nudity from sexuality, challenges the objectification and commercialization of bodies, and affirms embodied human dignity without imposing fear or shame.

Whether one accepts this argument or not, it highlights the essential question: does contemporary Christian teaching about bodies promote virtue, or does it reinforce dysfunction?

Berrimans Bare All

Berrimans Bare All